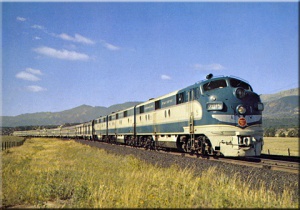

The Montana Rail Link (MRL) is a privately held Class II railroad operated out of Missoula, Montana. The MRL is a unit of the Washington Companies and operates on trackage originally built by the Northern Pacific Railway. MRL runs between Huntley, Montana and Spokane, Washington, passing through Missoula, Livingston, Bozeman, Billings, and Helena, and connects with the BNSF on both ends of the line, and also in Garrison, Montana. The railroad has over 900 miles of track, serves 100 stations, and employs 1,000 personnel, making it one of the largest Class II railroads in the country.

MRL got it’s start in 1987 when BNSF agreed to lease its former Northern Pacific main line between Billings, Montana and Sandpoint, Idaho. This new line was to be operated by Dennis Washington, who named it Montana Rail Link. Thus the MRL was born with over 900 miles of track.

Since the MRL line is connected to BNSF at both endpoints, a significant portion of MRL traffic is actually complete BNSF units, where MRL receives the train at one end and passes it back to BNSF at the other end. MRL also operates several local trains to distribute local freight, mainly forest products and grain, along its lines. The Gas Local is another significant MRL train, operating between Missoula and Thompson Falls, to bridge a gap in a long-distance gasoline pipeline.

The MRL is known to be a very well-run railroad, and has become so profitable that they recently completed a purchase of 25 new EMD SD70ACe locomotives. This new purchase added modern power to an already large fleet of EMD locomotives operated by MRL. These new SD70ACe locomotives are intended to replace aging SD40 and SD45 locomotives on trains crossing the Rocky Mountains over the continental divide at Mullan Pass near Helena, Montana, and Bozeman Pass near Bozeman, Montana.

Although the MRL is a very well-run railroad, they are not immune to disaster. On February 2, 1989, one of the most severe accidents in MRL history occurred. 48 decoupled rail cars rolled into Helena hitting a parked work train. The train caught fire and exploded, extensively damaging nearby property. Windows were blasted out up to three miles away from the impact, and most of the city lost power, with residents being forced to evacuate in subzero weather.

The cars were decoupled as engineers opted to switch the lead engine of a train because it lacked a working heater. Unfortunately the rest of the train started to roll and didn’t stop rolling until they hit a parked locomotive in Helena. A tank car carrying isopropyl alcohol caught fire, sparking an explosion in a adjacent tank of hydrogen peroxide. Cleanup was hampered by the cold, as it was minus 28 with a wind chill of minus 75 outside at the time. Both people and machines froze up in the bitter cold, but in the end there were no injuries reported during the disaster. According to one of the volunteers, “In the end, it was more of an adventure than a tragedy.”